17 September 2009

Great Teacher Professional Development at Pelham Elementary School!

17 September 2009

On September 17, 2009, approximately 35 elementary school teachers entered the world of science from a different viewpoint. Some explored with the eyes of a first grader, a 6-year-old, and others were more seasoned veterans on the elementary scene, fifth graders, or 10-year-olds. These teachers had all been asked to attend a workshop on the inquiry method of teaching science, presented by Fiona McDonald, a professor in the Education Department at Rivier College, David Burgess, a professor in the Science Department at Rivier College, Rebecca Cummings, a fifth grade teacher at Pelham Elementary, and Laurel Plouffe, a fourth grade teacher at Pelham Elementary.

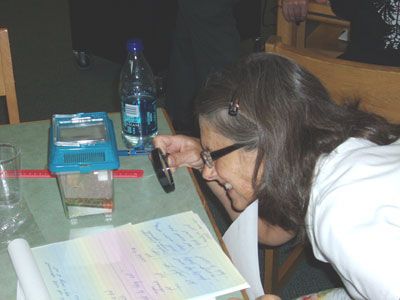

After many weeks of frustrating schedule changes and meetings about reading strategies these teachers were now free to explore and indulge in simple observation and investigation. These teachers were asked to focus not just on science, but the science of teaching during a time when there seems to be no time left to meet all the requirements. They arrived expecting a lecture and powerpoint presentation but were handed magnifying glasses and drawing paper. They were asked to draw what they thought a cricket looked like, not realizing that this was the beginning of the first phase of inquiry: Exploration. Then out came the real crickets. Just like elementary students, they were excited and nervous. Would they have to touch them? How will they get them into the cups? What would the principal think if she could see them now?! But the mystery of the cricket grabbed them and they observed, drew pictures, made labels, and reported to the rest of the group, developing questions as they discussed what they noticed. Without even realizing it, they were entering the next phase: Investigation and Data Collection.

Enter: the materials! These teachers were eager to feed the crickets even though they did not know what they ate, design habitats for them even though they were uncertain what a cricket prefers, and wonder at the purpose of the wings and other anatomy. They collected sod, dirt, carrots, celery, syrup, water, and other simple ingredients for their experiments. Just like a bunch of children under the age of ten, these teachers were engaged in trying to answer their own questions, the theory of connection that is the foundation of inquiry. They were not only engaged, they were invested in finding answers and along the way many new questions were excavated.

Then came the discussions or phase three of inquiry: Sense Making. As a group, or class, discoveries and results were shared, new questions written down, charts, graphs, and reports developed. It was a lot to accomplish in a two hour workshop. The same process can take weeks in a classroom, but the knowledge is lasting, the answers grounded in experience. These teachers left with a renewed energy for teaching science that is experiential more than didactic.

Given the revised GSEs and their emphasis on science processing skills along with content knowledge, inquiry in the classroom is naturally comfortable for students and incredibly important to the state of education. It is not for the controlling at heart. Teachers are more facilitators than lecturers, giving up the control to more meaningful experiences, guided the inquiry and allowing students the freedom to discover, explore, and wonder at their world as they collaborate to make connections with each other's findings and prior knowledge. During a time when all that is outside the classroom seems to be inhibiting the teaching process, these educators were given the opportunity and freedom to wonder for themselves, and then discover a role they may have been missing.